I was surprised, while reading Rebecca Solnit’s fascinating Infinite City: A San Francisco Atlas, to realize that I probably know substantially more about the history of Texas than I do about the history of my native San Francisco.

Of course, this realization should hardly have come as a surprise. After all, I’ve lived in Texas for more than half my life, whereas I left California at age seventeen, for college, and never moved back. Moreover, I spent more than half of my time in Texas working for the Texas State Historical Association, mostly researching and writing local history.

Still, it was a little bit of a shock. Despite my recent purchase of a spiffy pair of Lucchese boots, I still frequently think of myself as a Californian, not a Texan. Texas is where I live, but California is where I’m from, and that can be a significant difference. Especially in the South (and Texas is in many ways as much a part of the South as of the West), where you’re from—your “people,” your frame of reference—is still as important as who you are. But while I retain vivid, detailed mental and sensory images of San Francisco and the Bay Area—the sights, the sounds, the smells, and, yes, the tastes—I don’t really know how and why they came to be. In Texas, on the other hand, I learned a lot of the stories before learning the places they explain.

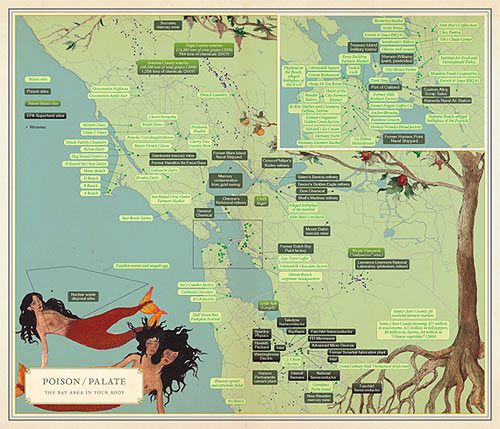

Solnit’s book presents both foreground imagery and background narrative. It is a series of maps and essays which manifest unexpected symmetries or contradictions: “Monarchs and Queens,” which simultaneously maps butterfly populations and sites significant in the history of the city’s queer population; “Poison/Palate” (above), which juxtaposes some of the Bay Area’s leading “foodie” establishments (Chez Panisse, Niman Ranch, etc.) with nearby mercury mines, oil refineries, chemical plants, and other sources of toxic pollution; and so on.

In reading and looking at this beautiful book—and it really is beautiful—I have learned a lot of local history, and also experienced that rush of nostalgia that accompanies any return, be it literal or literary, to your homeland. Just seeing the names on the maps, the extant and (especially) the long gone—Playland at the Beach! the Surf Theater! Winterland! Zim’s!—brought on a shiver of memory worthy of a Proustian madeleine. As Solnit writes, “the longer you live here, the more you live with a map that no longer matches the actual terrain.” She notes that the residents of Managua, Nicaragua, long after an earthquake that destroyed much of the city, “gave directions by saying things like, ‘Turn left where the tree used to be.’”

Similarly, my San Francisco is a palimpsest, an accretion of layers and memories, things and people living and dead, real and fictional—Emperor Norton and Sam Spade, Lawrence Ferlinghetti and Harry Callahan, and countless others. All of them were and are integral parts of where I’m from.

But that very notion of being from someplace is somewhat vexed. Locals say “I’m from here” all the time, but to me saying you’re from someplace usually implies motion, absence, a sense that you’re no longer there—that you’ve left it behind. In the United States, we have traditionally defined ourselves as an entire nation of people who are from somewhere else. My mother was born in Italy and my father in Brazil (though his parents were born in Scotland and Austria), which makes me about as American as you can get. After all, even the so-called Native Americans who were here before European contact originally came from somewhere else, presumably across the Beringian land bridge in pursuit of mammoth and bison.

In a fundamental sense, then, ours is a culture built on the sense of limitless opportunity awaiting us just beyond the horizon, just over that next rise. We have never stayed put, geographically or socioeconomically: the Louisiana Purchase, Manifest Destiny, the Mexican War, the California Gold Rush, the Civil War, and the Dust Bowl all pushed or pulled the new nation westward, across the continent, and we still seem to believe that, if we really make a hash of things where we are now, we can always pick up and move on to some uninhabited place (traditionally further west) where we can start fresh.

And some astonishing transformations did indeed take place out on that peripatetic frontier: a poor boy from Kentucky by way of Indiana and Illinois turned into Abraham Lincoln, an itinerant river pilot and printer’s apprentice from Missouri headed west and turned into Mark Twain, and so on. Even after Frederick Jackson Turner famously proclaimed the end of the frontier in 1893, our restlessness did not cease. In the twentieth century, the promise of economic opportunity and escape from Jim Crow drove the great migration of African Americans from the South to the north and west. Our current president, a son of Kansas and Kenya who was born in Hawaii and spent part of his childhood in Indonesia, is merely the most recent testament to the persistent power of the American notion of mobility, whether upward or westward.

Back to the Left Coast. In Infinite City, Solnit writes, “A city is a particular kind of place, perhaps best described as many worlds in one place; it compounds many versions without quite reconciling them, though some cross over to live in multiple worlds—in Chinatown or queer space, in a drug underworld or a university community, in a church’s sphere or a hospital’s intersections.” This is inarguably true of San Francisco, or for that matter any city; I would only add that it is no less true of a farm, a rural village, or any place that has borne the prints of generations of human existence. Like, say, Madroño Ranch.

All maps, even ones as imaginative and beautiful as the ones in Infinite City, are by definition reductive. They represent reality in two dimensions; we experience it in (at least) three. Maps, in other words, lack depth, and depth is what makes us and our world real. We don’t inhabit places flatly (though we certainly inhabit plenty of flat places!), but in depth, both geographical and temporal.

That depth is what we hope to gain personally at Madroño Ranch and also encourage in others, but we know we cannot simply will it into being. It grows and accumulates over time, and with care and effort; it is, in fact, a kind of rote learning, going over the same ground again and again, literally and metaphorically, until you have worn a track into the surface. John Muir noted that “Most people are on the world, not in it”; one of our hopes, now that our Austin nest is empty and we’re at the ranch more often, is that we can gradually learn to live and move in, not just on, this small part of the planet.

This is why Heather has grown increasingly ambivalent about travel; the world is full of fascinating places, but we’ve barely scratched the surface of our own. We hope it’s not (or not just) provincialism, but we want to be here.

—Martin

What we’re reading

Heather: Adam Gopnik, Angels and Ages: A Short Book About Darwin, Lincoln, and Modern Life

Martin: Steven Rinella, American Buffalo: In Search of a Lost Icon

this is wonderful, Martin, and so in tune with what I'm working on.sort of military brat manifesto for younger readers.you don't REALLY appreciate how much you're defined by the question "Where are you from?" until you don't have a good answer. love the video too!

ReplyDeleteThis speaks to me in so many ways. Home is landscape and people and stories and feeling comfortable, I think. But is home where we're from? Anyway, you've got me thinking.

ReplyDeleteThank you for reminding me of the class I used to teach called "Identity and Community" where we spent an entire unit asking so many of these questions... "Are we where we are from?", "How does place define us?", and so many other questions. And personally, why do I always answer the "Where are you from?" question with, "Well, I was born in New Orleans, but I grew up in California, and now I've lived in Texas longer than I lived in either of those places." Perhaps I don't really know where I'm from!!

ReplyDeleteDo you understand there's a 12 word phrase you can tell your partner... that will induce intense emotions of love and instinctual appeal to you buried inside his chest?

ReplyDeleteThat's because deep inside these 12 words is a "secret signal" that fuels a man's instinct to love, please and care for you with his entire heart...

12 Words Will Trigger A Man's Love Instinct

This instinct is so built-in to a man's genetics that it will make him work better than before to love and admire you.

As a matter of fact, fueling this powerful instinct is absolutely essential to having the best possible relationship with your man that once you send your man a "Secret Signal"...

...You will immediately find him open his soul and heart for you in a way he never expressed before and he'll identify you as the one and only woman in the galaxy who has ever truly understood him.